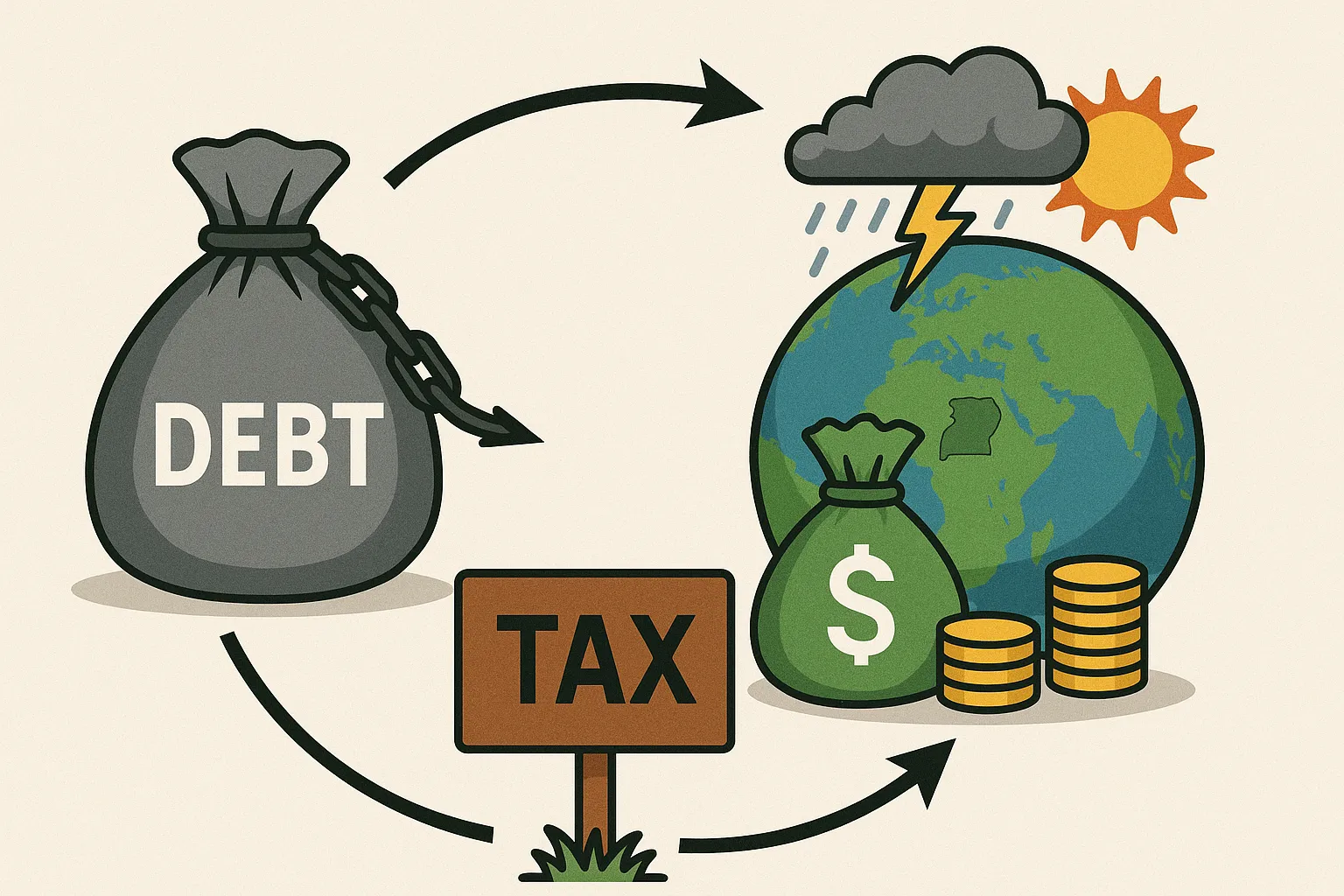

Debt-Tax- Climate Finance trifecta challenge

Debt-Tax climate

Uganda, like many developing nations, is grappling with a complex interplay of economic and environmental challenges, being ranked as the 12th most vulnerable country (worldwide) to climate change impacts and the 163rd readiest to deal with these impacts out of 192 countries assessed by the ND-GAIN Country Index 2022.

This is exemplified by the extreme weather events manifested through erratic rainfall, floods, and prolonged dry spells strongly impacting the largely rainfed agriculture sector by decimating the production and productivity of crops and livestock.

The three challenges of debt, tax, and climate finance are linked together. Uganda has a significant debt of USD 28.89 billion, a tax system that struggles to raise enough money and an urgent need for funding to address climate issues. The large debt makes it hard for the government to invest in climate projects. The low tax revenue limits what the government can do about climate change.

At the same time, climate-related disasters disrupt certain economic activities, which reduces tax income. According to the United Nations Development Programme on climate finance in Africa 2024, climate change damage is estimated at US$ 38 trillion annually by 2025, and a 12% decrease in global income related to farming, infrastructure, productivity, and health.

Climate financing involves funds and investments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, adapt to climate change, and promote sustainable development. The finances are sourced from public and private sources to address climate adaptation and mitigation measures; through the conventional annual national budget channeling the funds to Ministry of finance being the custodian of the and to the Ministry of Water and Environment Uganda to support climate-resilient projects recently decentralized Local Climate Adaptive Living Facility to such adaptation (LoCAL) at local governments, multilateral international institutions which lead climate finance like the Green Climate Fund( GCF), Adaptation Fund(AF), Least Developed Countries Fund(LDCF), and Global Environment Facility( GEF).

Additionally, there are bilateral partnerships with governments, such as GIZ- German government, AFD-French government, JICA-Japanese government, and USAID-US government, among others offer loans and grants to support climate initiatives. According to the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), developing countries are particularly vulnerable to climate-related risks and often spend more than twice as much on debt servicing in their fight for climate finance.

As of April 2025, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reported that global public debt is now over USD 100 trillion, projected to be 95.1% of the GDP by the end of 2025. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) reports that public debt in developing countries reached US$ 29 trillion in 2023, growing twice as fast as in developed economies since 2010. This amount constitutes 30% of the global public debt, which totals US$ 97 trillion. In the context of climate finance, developing countries face the dual challenge of debt repayment and financing climate initiatives.

A recent analysis by the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) of 58 developing countries reveals that in 2022, these countries spent US$ 59 billion servicing debts, while only receiving US$ 28 billion in climate finance. Of this climate finance, just over half (US$ 14.8 billion) was provided as loans rather than grants, meaning that debt repayments exceeded the assistance received from bilateral foreign aid, of which climate finance is a part.

For instance, Uganda’s risk of debt default is moderate, with US$ 1,928.6 million allocated for debt servicing and US$ 1,357.5 million for climate finance in 2022. Of the climate finance, 51% (US$ 1,357.5 million) came from loans, and 49% (US$ 686.1 million) from grants.

In light of this, the adoption of the Paris Agreement by developed countries pledging to mobilize US$ 100 billion per year till 2025 to support a good course for climate action for developing countries turns out to exacerbate the debt burden through the non-concessional loans with high-interest rates and exchange rate risks far worsen the debt situation which limits the fiscal space for climate action initiatives.

Climate change mitigation and adaptation require significant public investment. For instance, the East African Community (EAC) needs $181 billion from 2021 to 2030 for climate impacts, with Uganda’s share of approximately US$ 28.1 billion $17.7 billion for adaptation (63%) and US$ 10.3 billion for mitigation (37%). This funding challenge strains government budgets as climate impacts negatively affect sectors like agriculture and tourism, leading to reduced tax revenues. These shortfalls in revenue and fiscal indiscipline force the government to borrow, limiting its ability to invest in climate-friendly initiatives and infrastructure.

Uganda’s fiscal deficit forces the government to borrow to meet its financial obligations. The country faces shortfalls in revenue, looking at the first quarter of the year 2025 and has a low tax base compared to the potential size of taxpayers.

This situation is exacerbated by the large untaxed informal sector, inefficiencies within the tax system, and a general unwillingness to pay taxes. At the beginning of the year, 2024, the Uganda Revenue Authority (URA) initiated a tax collection drive in the Central Business District (Kiikubo) to utilize the Electronic Fiscal Receipting and Invoicing System (EFRIS).

However, the adoption rate of this system has faced resistance from the local business community. Such oversight contributes to the limited revenues collected. To address these issues, the government should explore innovative mechanisms for financing its obligations, particularly concerning climate initiatives. For example, leveraging the now yet to be operationalized carbon markets could generate additional revenue. However, this approach may not be equitable, as it could serve as a scapegoat for polluters and is not necessarily sustainable in the long term.

In conclusion, it is imperative for the government to first understand the complex interplay of debt, tax, and climate finance for effective decision-making through capacity building, and pursue grants for climate finance as they look for local sustainable financing mechanisms for climate actions given the change in policies, also advocate and explore locally-led alternatives such as community led public private partnership that prioritize self-reliance, equity, and sustainable development agenda of their countries, especially in the global climate summits regarding climate change and financing.